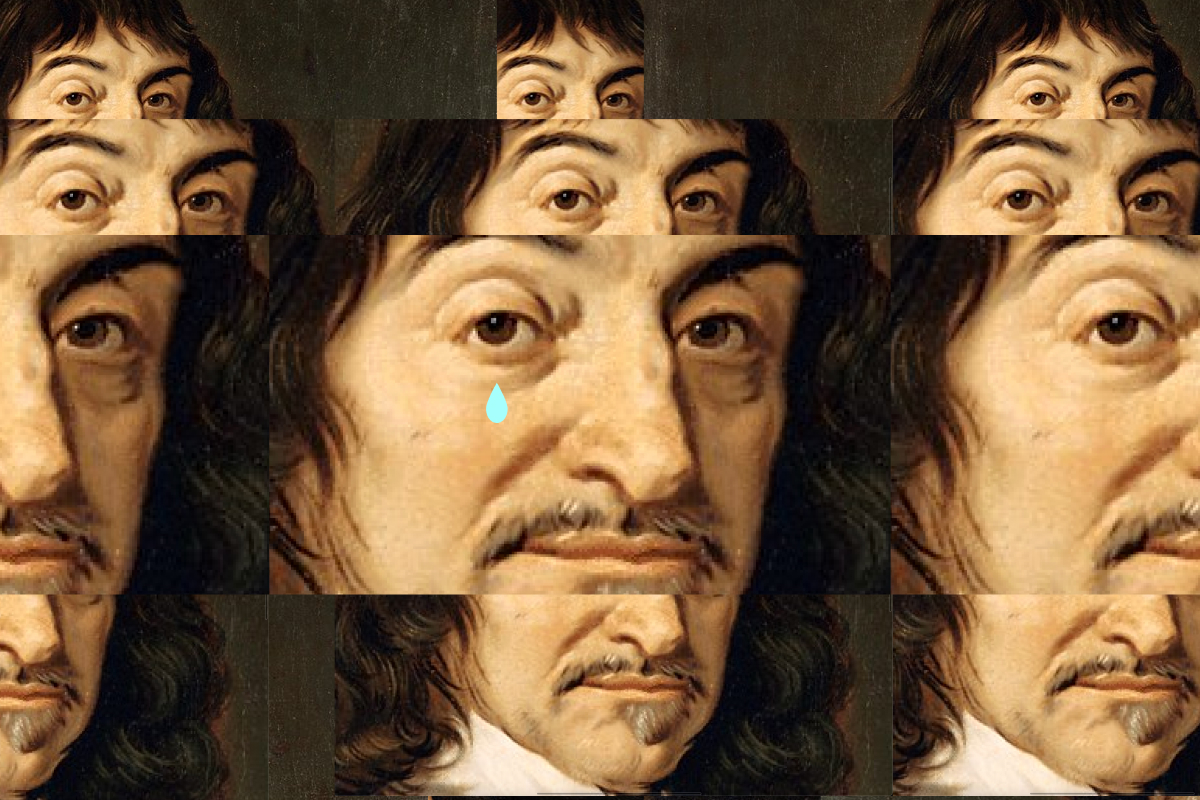

Few lines have been quoted more, by nerds and jocks alike, than this one:

“Cogito, ergo sum” — I think, therefore I am.

Declared by René Descartes in the 1600s as the first principle of his philosophy, while searching for an inkling of certainty amongst the unreliability of our experience in a Demon-laden world of illusions.

It became a fundamental element of Western Philosophy, placing thinking above any other activity, and its source — the thinker — at the center of it all.

Yet, as helpful as it’s been in humanity’s quest for knowledge, from a metaphysical perspective, Descartes’ statement seems more like the perfect recipe for an anxiety attack rather than a source for wisdom. On top, it reduces the totality of our being to a single function.

As it turns out, I’m hundreds of years late to the debate.

Way before Descartes, philosophers and mystics, as well as medieval scholars, had already questioned the value of the intellect.

To the Pyrronists of ancient Greece, epoché — the suspension of judgement — was the only way of achieving freedom from worry and anxiety. They basically encouraged people to stop claiming knowledge about what can’t be known.

Peace, not certainty, was the prize.

Later came Nietzsche, doubling down against the necessity of an “I” in the thinking process. You can prove this for yourself by trying to not think of something right now. Given enough time, thoughts will arise on their own without any action from your part.

Heidegger argued against the irreducibility of existence to thought, thinking being only one mode among many. Similarly, Merleau-Ponty pointed to the body as our anchor to the world — perceptions and bodily experience are as indubitable as thought.

From a language perspective, Wittgenstein talked about how language itself frames the way we conceive reality. While the structure of a language might lead us to believe that “I think” is naturally true, reality might be more like “there is thinking”.

Finally, at the biological level, neuroscience has shown us that thinking is a process that emerges from neural activity, body chemistry, and environment.

To be fair, Descartes’ goal wasn’t metaphysical. It was epistemological. He wanted to find a solid base upon which knowledge could be established.

Still, however distinct his goal was, cogito is to this day a primordial element of modern society and, by extension, shapes our sense of well-being. Therefore, it’s important to question how the emphasis on thinking above everything else affects our lives.

Isolating oneself in the crevices of our mind alienates us from the rest of existence. Thinking, as real as it might seem to the rational mind, is pretty much the same as the other processes Descartes discarded as illusions with his logic.

Why, then, restrict existence to thought? If “I think, therefore I am” is true, then “I feel/see/taste/hear/smell, therefore I am” is just as valid.

The thing is, we aren’t merely brains in a vacuum separate from the world. The world influences us as much as we’re influenced by it — a closed system where the senses lead to thought, then action, finally to be fed back into the system.

This speaks to the weight of one’s presence, the gravity with which our mere existence pulls everything around it.

Whereas Descartes proposed a method to lean away from uncertainty, what I’m looking for now is a method to lean fully into it — to embrace fully the experience of being without need for a justification:

"Sum, ergo sum" — I am, therefore I am.